The Society at the College Art Association Conference, online,

Decentering Collecting Histories

Chair: Dr. Stacey Pierson, SOAS

As an affiliated member of the College Art Association, the Society hosts one session, this year still online. This is one of the most important events for art historians, who wish to offer interdisciplinary sessions, often addressing questions from a wide geographical or historical perspective. This year’s session, proposed and chaired by Steering Committee Member, Dr. Stacey Pierson, on recent research into the history of collecting, aimed to move from concentrating on collecting practices by European and American collectors to a much more varied understanding of the global circulation and appropriation of works of art. This approach has been much enhanced by interest in contemporary collecting practices both in the West and in emerging markets throughout the world. However, the history of collecting has been slower to consider non-Western collectors, especially those beyond a restricted canon of examples. This session asked what it would mean to de-center the history of collecting, whether by moving into unfamiliar geographies, recovering the agency of overlooked (often non-European) actors, or reflecting on alternative epistemologies, namely different ways of classifying and exhibiting works of art. What methodologies and what sources are available to those scholars seeking to ‘decenter’ collecting history? How do de-centered approaches force us to rethink definitions about collecting as a cultural activity? We invited proposals from scholars who see their research as lying beyond, and problematizing, more established topics in art history and the study of historical art markets. For instance, whilst much existing research has been focused on the dynamism of collecting in capital cities, we welcomed research that rethinks the relationship between core and periphery, or considers the interplay between metropoles, provinces and spaces of colonial occupation.

This panel sought to showcase innovative new work which, by interrogating topics often pushed to the margins of collecting history, also challenges assumptions about what constitutes the ‘center’ of the field.

Here are summaries of the four papers from the conference.

The Secret Acquisition Team: Hong Kong’s Role in the Formation of the Palace Collection

Dr Raphael Wong, Associate Curator, Hong Kong Palace Museum

Collecting as Collaboration: Making of the Hon. Henry Marsham Collection of Japanese Ceramics in Kyoto and Maidstone, 1882–1908

Dr Ai Fukunaga, Ishibashi Foundation Assistant Curator for Japanese Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Competing Agendas between Colony and Metropole: The Early Years of IFAN’s Museum Collections, Yaëlle Biro, Independent Scholar

‘Decentering collecting histories by mapping transnational mobilities: French impressionism in Wales’, Dr Samuel Raybone, Aberystwyth University

The Secret Acquisition Team:

Hong Kong’s Role in the Formation of the Palace Museum Collection

Dr Raphael Wong

Introduction

From 1949 to 1956, the Acquisition Team rediscovered more than a hundred works of early Chinese painting and calligraphy scattered throughout private collections in Asia—Hong Kong, in particular, America, and Europe. Having facilitated the acquisition of almost sixty works now in the Palace Museum, the team was directly responsible for the formation of the museum’s encyclopaedic collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Despite its monumental achievements, little research has been conducted on the history of the team. The recent publication of new materials—including memoirs written by a former director of the Palace Museum and by collectors as well as, more importantly, letters and telegrams written by the member of the team that were auctioned in Hong Kong in 2019—necessitate a re-examination of the team’s activities.

Founding of the Acquisition Team

The history of the team can be traced back to May 1949, when Zheng Zhenduo (1898–1958), later director of the Bureau of Cultural Relics of the People’s Republic of China, discussed the need to retrieve lost historical artefacts. As a British colony with a free market economy close to mainland China, Hong Kong became a key strategic site for acquiring and building China’s national collection of antiquities.The determination of the Chinese government to retrieve lost treasures in Hong Kong was probably reinforced by the successful acquisition in that city of two of the “Three Rarities” of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–1795) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). In 1953 the Chinese government decided to formally appoint a team to pursue acquisitions in Hong Kong. Xu Bojiao (1913–2002), more commonly known as P. J. Tsu, was appointed to the team. The team targeted ancient books and paintings of pre-Ming (1368–1644) vintage that were both relatively rare and easily dispersed. Team members were responsible for different tasks: Xu Bojiao oversaw identification, authentication, appraisal, and price negotiation. Shen Yong and Wen Kanglan were in charge of payments and logistics. They worked in parallel with Zheng Zhenduo and experts in China.

Politics, Competitors, and Forgeries

The acquisition team faced many challenges. One was the need to work in secrecy. This was partly due to the wider political environment, and partly to avoid affecting the price of the works they were attempting to recover. Letters written by Xu Bojiao tell us that the team tried to acquire paintings from Japan, Europe, and America, where they faced fierce competition. According to the letters, numerous paintings published in the 1954 book Chinese Landscape Painting by Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008) were purchased in Hong Kong. The acquisitions were complicated by the appearance of forgeries in the market. The newly imposed Law for the Protection of Cultural Relics, which prohibited the removal of antiquities from China, further complicated matters.

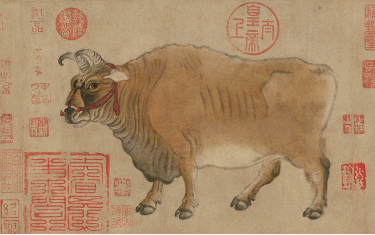

Detail of the painting, Five Oxen, The Palace Museum

The Making of Masterpieces

The team’s role in defining the Chinese painting canon is vividly demonstrated by the journey of a painting: Five Oxen. The Five Oxen is regarded as the only surviving painting by Han Huang (723–787) of the Tang dynasty (618–907) and one of earliest extant paintings on (mulberry) paper. The painting is believed to have been removed from the Imperial City by the Eight-Nation Alliance stationed there in the early 1900s. When it emerged in Hong Kong, it was in the possession of a man named Wu Hansun. Xu Bojiao saw the value of the painting and convinced the experts on the mainland to acquire it. Walter Hochstadter (1914–2007), a dealer active in the United States, was also trying to obtain the work. Eventually, the painting was acquired and brought back to its former home, where it was extensively conserved. Five Oxen entered the collection of a national museum in the public eye and was transformed into a first-class “national treasure”.

Conclusion

Acquisitions and donations contributed significantly to the growth of the modern museum’s collection. Despite the challenges of politics and the market, the acquisition teamsuccessfully recovered a considerable number of works of pre-Ming origin. These constitute an important part of both the collection of the Palace Museum and the canon of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Among the Chinese painting and calligraphy in the museum today, they continue to occupy an important place that represents and defines Chinese art, culture, identity, as well as the international status of the Palace Museum.

Collecting as Collaboration:

Making of the Hon. Henry Marsham Collection of Japanese Ceramics in Kyoto and

Maidstone, 1882–1908

Dr Ai Fukunaga

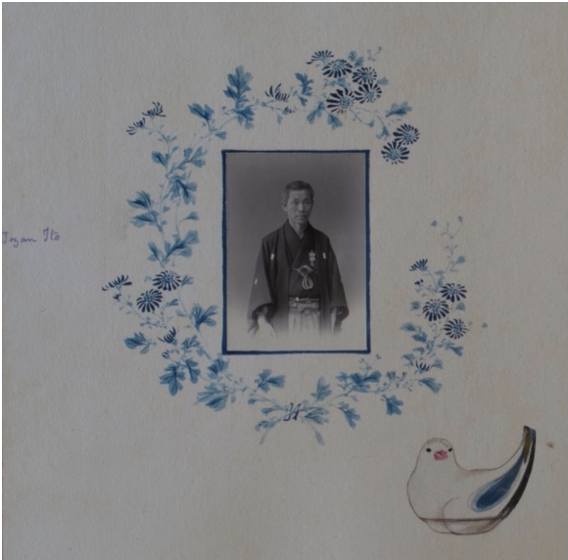

Fig. 1 Itō Tōzan, portrait of Tōzan and painting of his work, album annotated by Henry Marsham,c.1906, Maidstone Museum, Kent, MNEMG.1931.30(2). Photographed by Author. ©Maidstone Museum.

In the 1900s, Hon. Henry Marsham (1845–1908), a British collector and businessmanintensively collected Japanese ceramics in Kyoto. His collection at the Maidstone Museum,Kent is one of the most important Japanese ceramics collections outside Japan for the varietyand quality of domestic products from different kilns, featuring stoneware produced in theAwata region of Higashiyama, Kyoto. Marsham’s distance from London’s art circles and absence of publication not only left him as a forgotten collector but also obscured those who were involved with the creation of his collection.

Based on archival and material research in Kyoto and Maidstone, this paper revealed howlocal agents of the two cities supported the development of the Marsham collection andknowledge of Japanese ceramics. Adopting Actor-Network Theory, collecting is defined as aresult of communication among actors in a collecting network, locating a collector as one ofthe elements of collecting—composed of various connections with objects, people, placesand institutions.

Illustrated by Marsham’s three travel albums, the first part of the paper explored how Kyotolocals contributed to his collecting. Hayashi Shinsuke IV, one of the most famous dealers in Meiji Kyoto, not only sold ceramicworks but also stored the ceramic collection for Marsham. The strength and range of Hayashi’s shop—lacquerware and everyday utensils including ceramics—were also considered to have shaped Marsham’s collecting, which shifted from lacquerware to ceramics made for the Japanese market by 1906. Itō Tōzan (1846–1920), who later became an Imperial Household Artist shared the same interest with Marsham in old Awata ware as a ceramic artist who tried the revival of the traditional taste with new technology. (Fig.1) Tōzan collected old Japanese ceramics as references. Tōzan’s paintings and ceramic works in the Marsham collection demonstrate the tie between the artist and the collector.

Marsham frequented the Reikanji, an Imperial Buddhist Convent and consulted the temple’scollection. The connection between the collector and the temple implies that he might have seen ceramics specifically made for the imperial families, which can be found his collection.The Miyako Hotel, Marsham’s accommodation in Higashiyama, connected the collector to the arts, people, and places of the region. An Awata potter, Hōzan Shōhei (1848–1937) made ceramics from the clay that Marsham picked up from the garden of the hotel. Hirooka, a Japanese guide assisted Marsham’s collecting by working between the hotel, dealers, and the collector. The hotel even had a gallery run by Kyoto dealers. The hotel published guidebooks that recommended Hayashi and suggested itineraries to temples including Reikanji.The second part of the paper looked at the context of collecting for Maidstone to which he had a long family connection.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Display case for Iwakurasan ware, Borough of Maidstone, Museum, Public Library, andBentlif Art Gallery, Report of the Curator and Librarian. For the Year Ended October 31st, 1907 (Maidstone: Water Ruck, 1908), 31, Plate II. © Maidstone Museum.

Marsham’s collection developed with the Maidstone Museum, Library and Bentlif Art Gallery whose facilities and contents were largely contributed by townspeople. East Asian collections have been the strength of the museum, competing with other national and international ones. Various actors in Maidstone collaboratively realized the accommodation of the Marsham collection. J.H. Allchin, the Curator and Librarian facilitated the transfer of his collection to Maidstone. Special display cases for the collection was prepared with theof the borough of Maidstone and private trustees of the Bentlif Art Gallery (Fig. 2) Marsham’s sister Anne took an administrative role in the process of making Marsham’s loaned collection into a public collection after his death.

In London, from the mid-1870s, Augustus W. Franks (1826–1897) collected Japanese ceramics systematically. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Edward S. Morse’s (1838–1926) collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with over 5,000 objects established a firm status as a complete set of Japanese domestic ceramics. The Marsham collection’s coverage of diverse kilns in Japan indicates these collections had an impact on his collection. However, Marsham updated his knowledge with direct communication with Japanese potters and his own research in Kyoto. Moreover, he branded his collection by the range and quantity of Iwakurasan ware produced in the Awata region, which had never been collected on a large scale.

Understanding the entire picture of collecting, the Marsham collection speaks to us various stories surrounding the objects. Giving what had been thought of as the peripheral equal attention to the central, this research vocalized marginalized agents, regionally or art historically, as active players of collecting.

Competing Agendas between Colony and Metropole: The Early Years of IFAN’s Museum Collections

Dr Yaëlle Biro

Until recently, my research has focu sed on collecting practices of African works in Europe and America at the turn of the 20th century. My PhD dissertation established the commercial networks of African objects in Europe and the United States at the turn of the 20th century and the roles of a number of European and American dealers, critiques, and other enthusiasts in shaping the African art canon (Biro 2010). In 2017, as I was reworking my thesis to make it into a book (Biro 2018), the glaring absence of Africa from that study became painfully apparent. While I had carefully followed the trajectories of many works and their status as they changed in the West from ethnographic curiosity into works considered for their aesthetic appeal, very few of the archives I consulted had allowed me to clarify the specific collecting histories of these works on the continent from which they stemmed. Most often, the leads brought me as far as an auction house in London, or a sailor in Marseille, a colonial officer in Belgium or an ethnographica vendor in Hamburg. The first part of the works’ trajectories, however, from the place of their creation in Africa to Europe’s harbors or capital cities, could only be speculated in view of the timeperiod’s colonial history, with the risk of oversimplifying. Thus, after having studied the secondary art market for African objects, I wanted to initiate a research investigating the works’ commercial networks on the continent. This paper originates from this impetus, but the research is only in its infancy and merely presents initial thoughts and forays into the vast topic: the pandemic has largely thwarted my efforts to consult key archives over the past two years.

The Society at the College Art Association Conference SP revisions_RW_SR_YB Doc2A.Albaret, Dakar. Postcard, Dakar – Le Musée, 1939. https://books.openedition.org/demopolis/558

My presentation pertains to the shaping of the collections of the Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (IFAN) in Dakar, Senegal, the then-capital of French West Africa (A.O.F), during the colonial era (much has been written on IFAN and its collecting practices. See in particular Adedze 1997, de Suremain 2007, Ndiaye 2017, and Bondaz’s extensive body of work, most recently Bondaz 2020). Founded by decree in 1936, the institut’s stated goal was to “stimulate scientific research in every domain and to ensure liaison and coordination” between research centers throughout the French colonial territories in West Africa. The center was located in Dakar, and regional research satellites were established in Saint-Louis, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea Conakry, Mali, Niger, Benin, Burkina-Faso, Cameroon, and Togo.While no actual museum opened before 1961, after the wave of Independences, the institute in Dakar as well as several of the satellite locations began assembling ethnographic, archeological, botanic, entomological and zoological collections shortly after their founding. In 1943, Théodore Monod, IFAN’s first director, provided one of the institution’s role’s earliest descriptions, emphasizing its function as a filter to enhance the collections of the metropole (Monod 1943, pp. 197-198, translation from French my own):

“The role of the colonial research organization will therefore be above all to accumulate first-hand material . . . to ensure its sorting, assessment, general study, and conservation for the specialists of the future. . . The more French laboratories and museums will receive materials already ‘trimmed out’, not encumbered with useless trivialities, the more enthusiastic they will be – and the more time they will find – to study with care and profitably what will be sent to them, and which then will really be worth the trouble. The African institute should therefore, positioned at the center of the circuit, . . . insure the liaison between the metropolitan citadels of science . . . and the outposts of the bush . . .”

This quote is explicit about IFAN’s original position as a filtering station of material culture, at the threshold between primary and secondary market, as it existed in West Africa between the 1930s and the late 1950s. In function, it responded to the desire of Paris’s Musée d’ethnographie (later Musée de l’Homme) to “establish itself as the central node of a network stretching across the empire” (Monroe 2019). IFAN’s very structure, however, complexifies the notions of “centers” and “periphery.” What should be considered the center? The metropole or Dakar, Dakar or its regional “satellites,” the latter being in fact at the forefront of the collecting processes

If IFAN was meant to be a filter of material for the metropole, historian John Warne Monroe recently underscored that its role was also to ensure some control over European ethnographers and dealers whose collecting practices were considered so intense by the early 1930s that they worried the colonial administration and amplified its desire to retain the continent’s material culture (Monroe 2019). As such, another of IFAN’s goals was to contribute to maintaining an exhaustive sampling of the colony’s material production in the colony (Bondaz 2020, de Suremain 2007). Such a discrepancy in the institute’s mission signals that the selection processes between what remained and what was sent to the metropole necessarily reveals competing agendas and individual priorities. Indeed, as a colonial institution located on the continent, the ethnographic objects that entered its holdings or transited through its walls came from a variety of sources that exemplify the range of actors of the period’s collecting practices: colonial administrators, missionaries, ethnographers, and a range of often anonymous African vendors.

I structured my presentation around three case studies that address the complexities of the trajectories of West Africa’s material culture between their place of acquisition to IFAN, and from there to the metropole. To do so, one of my examples focuses on the collection of IFAN’s satellite in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire (on the specificities of this collection, see for example Ravenhill 1996 and Bondaz 2020) while the two others consider works from Dakar’s holdings. I address the multiplicity of actors involved by varying the collecting context of the works: missionaries, art dealers, the director of the Abidjan satellite museum, a colonial officer, the head of IFAN’s archeology section, the curator in charge of the African collection at the Musée de l’Homme, and unidentified vendors from Mali and Guinea. Through these examples, I also consider the art market as it was established by the metropole and its impact on the dissemination of the works.

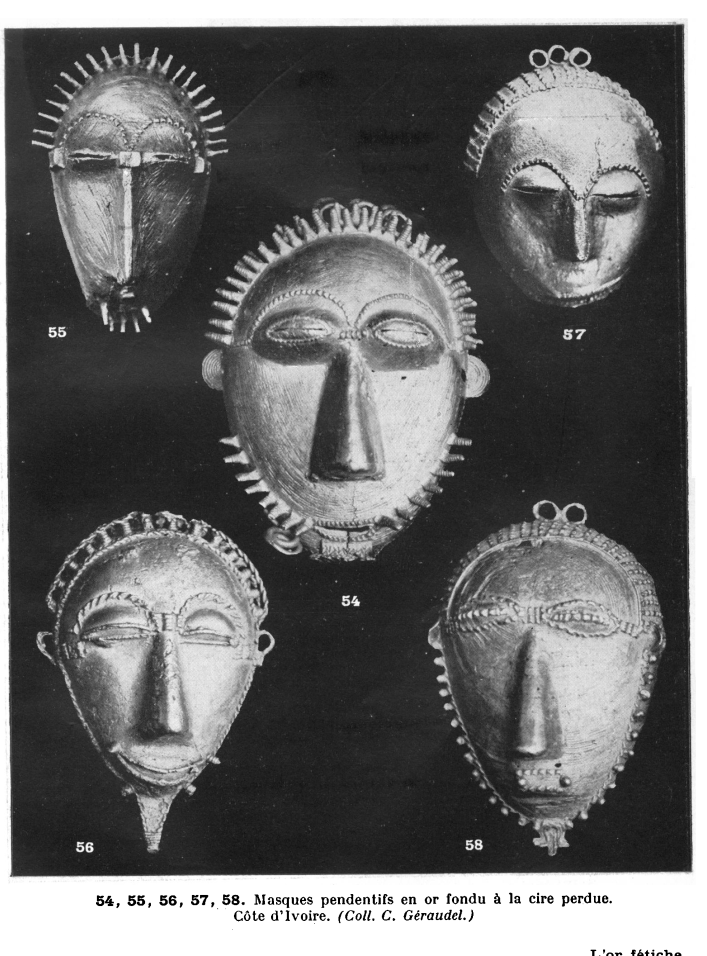

The first case study considers missionaries Fr. Michel Convers and Fr. Gabriel Clamens through the example of the group of works documented in the early 1950s in the northern Côte d’Ivoire town of Lataha, a pair of which would enter the IFAN collection in Abidjan while others would integrate the Euro-American art market through the intermediary of Swiss art dealer Emil Storrer (I draw here upon the work of Susan E. Gagliardi and her efforts to disentangle the complex trajectories of this group of works. See Gagliardi 2014 and Gagliardi & Petridis 2021). The second case study focuses on an important ensemble of forty-nine Baule gold ornaments, first assembled in Côte d’Ivoire by colonial administrator Claude Giraudel, and which entered the collection of IFAN in Dakar (see Bardon 1948, Ratton 1951) before some were transferred to Paris’ Musée de l’Homme collection and later were retroceded to Dakar in 2018 (outside of two works stolen in Paris in 2010).

Five Baule gold ornaments from Côte d’Ivoire in the Giraudel collection as published in Ratton 1951. The ornament in the upper right (Cat. 57) entered Dakar’s IFAN collection in 1948, was transferred to the Musée de l’Homme in Paris in 1967, and recently reentered the Senegalese national collections.

Finally, the third case study investigates a group of masks, crests, and figures from Guinea, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire, acquired in 1957 by the Dakar institution from unidentified vendors from Guinea and Mali in order to exchange them against archeological material held at the Musée de l’Homme (transaction mentioned in Bondaz 2020; and demonstrated through several letters between Raymond Mauny and Denise Paulme, April to December 1957, DA002040/18837 archives du musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac; individual objects’ records). Like the Baule gold ornaments mentioned above, this group of works was ceded back to Dakar in 2018.

These three case studies are a mere sample of interactions that reflect on the complex nature of the circulation of objects connected to IFAN during the colonial period. The collections as they stand today in Dakar or Abidjan are fascinating windows onto IFAN’s collecting processes and the institution’s legacies both through the objects that are present, those that never entered these collections, and those that merely transited through these holdings to the metropole (and, sometimes, back). Historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot poignantly stated: “The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility” (Trouillot 1995). We hope to further proceed with trying to read the gaps and silences in the collections of IFAN’s museums. Between the lines of the collections, in these negative spaces, lie the traces of the past generations’ selection processes and the roots of our understanding of these collections today.

References

Adedze, Agbenyega. Collectors, Collections and Exhibitions: The History of Museums in Francophone West Africa. UCLA, 1997.

Biro, Yaëlle. Fabriquer le regard : marchands, réseaux et objets d’art africains à l’aube du XXe siècle. Les Presses du réel, 2018.

—. Transformation de l’objet ethnographique africain en “objet d’art”: circulation, commerce et diffusion des œuvres africaines en Europe Occidentale et aux Etats-Unis, des années 1900 aux années 1920. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2010.

Bondaz, Julien. “« Echantillonner toute l’Afrique » : Les collectes coloniales de l’Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (1936-1960).” Trouble dans les collections, no. 1, Nov. 2020, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03339495.

De Suremain, Marie-Albane. “L’IFAN et la « mise en musée » des cultures africaines (1936-1961).” Outre-Mers. Revue d’histoire, vol. 94, no. 356, 2007, pp. 151–72, https://doi.org/10.3406/outre.2007.4289.

Gagliardi, Susan Elizabeth. Senufo Unbound: Dynamics of Art and Identity in West Africa. 5 Continents : The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015.

Gagliardi, Susan Elizabeth & Petridis, Constantine. “Mapping Senufo: Reframing Questions, Reevaluating Sources, and Reimagining a Digital Monograph.” History in Africa, 48, 2021, 165-209. doi:10.1017/hia.2021.5

Monod, Théodore. “L’institut français d’Afrique noire.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, vol. 14, no. 4, Oct. 1943, pp. 194–99.

Monroe, John Warne. Metropolitan Fetish. African Sculpture and the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick. “Le musée Théodore Monod d’art africain : du fonctionnalisme ethnographique au formalisme esthétique.” Art rupestre africain: de la contribution africaine à la découverte d’un patrimoine universel, edited by Richard Kuba and Hélène Ivanoff, 2017, pp. 149–55.

Ratton, Charles. “L’or fétiche.” Présence Africaine, vol. 1, no. 10–11, 1951, pp. 136–55.

Ravenhill, Philip L. “The Passive Object and the Tribal Paradigm: Colonial Museography in French West Africa.” African Material Culture, edited by Mary Jo Arnoldi et al., Indiana University Press, 1996, pp. 265–82.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press; 2nd Revised edition, 2015.

‘Decentering collecting histories by mapping transnational mobilities: French impressionism in Wales’

Dr Samuel Raybone

This paper argued that collecting can be understood as a transnational practice of translocation, translation, and transformation, wherein people, objects, and ideas are set in motion. Thus made mobile, they circulate around complexly entangled networks which permeate across national boundaries. The artworks and agents, concepts and capital, texts and epistemes, collectors and desires, narratives and discourses that collecting sets in motion find their way to unexpected places, whereupon they can become enmeshed in yet further connectivities, and can generate novel experiences and meanings that bear the stamp of this mobility, exchange, translation, and hybridization across and between cultures.

A transnational frame of reference and way of seeing was proposed as one means of decentering collecting histories, because it can disrupt the colonial narratives, center-periphery spatializations, and national hermeneutics that have often limited the study of collecting. By attending to mobilities that transcend political boundaries with the aim of recovering the complexity of global circulations, we can reveal the plurality, ambivalence, and hybridity of cultural practices on the so-called periphery (which have been suppressed by ascriptions of influence and imitation) and recover the creativity of overlooked collectors in overlooked places.

The ‘Loan Exhibition of Paintings’ held in the temporary national museum in Cardiff City Hall in 1913. Image: https://museum.wales/articles/1039/From-Industry-to-Impressionism–what-two-sisters-did-for-Wales/

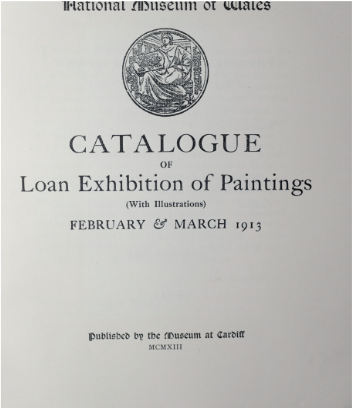

Claude Monet, San Giorgio Maggiore, Twilight, 1908. Purchased by Gwendoline Davies October 1912, exhibited in 1913, bequated to National Museum of Wales 1951. Photo: © Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales.

As a case study, the paper examined early twentieth century Wales, focusing in particular on the 1913 Loan Exhibition of Paintings – which mostly exhibited the collection of Gwendoline and Margaret Davies – posited as a crystallisation of myriad transnational networks and a catalyst for generative, productive translation and hybridization between cultures.

The Davies sisters’ collection was particularly strong in modern French paintings and sculptures, and was bequeathed to the National Museum of Wales in 1951 and 1963. Marginal to histories of the reception of impressionism in Britain that center on London, in Wales, where they are significantly better known, the Davies sisters’ collecting is invariably either lauded as a facet of Welsh national becoming (as ‘what two sisters did for Wales’), or critiqued as a foreign import, reflective of English rather than Welsh taste, and thus irrelevant ‘to our particular national story’.[i] This dynamic (assumptions of Welsh irrelevance combined with an exclusively national hermeneutic) is repeated across scholarship on the history of art and collecting in Wales more broadly, and indeed provided the conceptual framework in which the 1913 exhibitionitself was conceived and received.

Catalogue of Loan Exhibition of Paintings (with Illustrations) February & March 1913. Cardiff: Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru / National Museum of Wales, 1913. Photo: © Samuel Raybone

In the early twentieth century it was assumed (inside and outside Wales) that Wales had no art culture and the Welsh people lacked taste. Thus, aiming to remedy this national humiliation in the context of a revival of cultural nationalism (in which the Davies sisters participated), the exhibition was conceived to ‘direct’ the Welsh public in a more ‘noble standard of taste’ and ‘give stimulus to the long-delayed revival in Welsh art’[ii]. Yet, this positing of (French) impressionism as a catalyst for Welsh national culture entailed more conceptual and concrete translation than has heretofore been realised.

Via a close reading of the exhibition’s catalogue, the paper outlined the polyvalent and ambivalent epistemologies leveraged to introduce the Welsh public to impressionism, which was presented as both an art of scientific naturalism and emotional formalism, as both excitingly modern and reassuringly traditional, as both foreign and native. To explain this apparent incoherence without resorting to stereotypes of Welsh ignorance, the paper traced the transnational mobilities of the Davies sisters, their artworks, and their agents and advisors (who proposed and curated the exhibition), which took numerous forms (travel, education, criticism, art history, the art market, museum and selling exhibitions) and described a network linking Llandinam, Cardiff, London, Paris, and Venice. Via these connections, the Cardiff exhibition was able to leverage aesthetic and historical epistemologies generated through critical and commercial practices in London to mediate between their grand ambitions and the necessarily selective material they were able to display. Nevertheless, it was not a case of mere emulation.

The paper suggested that the disproportionate prominence of landscapes (in the collection and exhibition) – intimately associated with Welsh national identity – the ascription of educational value to impressionism – to elevate philistine Welsh taste and inspire insipid Welsh artists – and (the critics’ perceptions of) a special emphasis on abstract colour – which resonated uniquely with the Welsh thanks to their poetic, Celtic blood – together provided evidence of the translation and adaptation of those epistemologies imported from England.

In sum, the paper argued that the nuanced meanings and motivations behind the Davies sisters’ collection and display of impressionism are best understood to reflect complex interactions between the particularities of Wales and the ties that bound it to a much wider world.

[i]Oliver Fairclough, ed., ‘Things of Beauty’: What Two Sisters Did for Wales (Cardiff: National Museum Wales Books, 2007); Peter Lord, The Aesthetics of Relevance, ed. Meic Stephens, Changing Wales, (Llandysul: Gomer, 1993), 47.

[ii] First quotation from curator Murray Urquhart, speaking at the opening of the exhibition, quoted in “Masterpieces of Art. First Work of National Museum. Exhibition in Cardiff. Gallery Opened by Lord Mostyn,” The Western Mail, 5 February 1913, 6. Second quotation from curator Hugh Blaker, “The Loan Exhibition at the Welsh National Museum,” ibid., 12 February, 7.

For Raphael: If the activities of the acquisition team were secret, how were their purchases handled publicly? That is, were the works they acquired put on display right away and were they publicized?

For Yaëlle: As you showed, missionaries were actively involved in acquiring objects from the Côte d’Ivoire (and I imagine other places). Is there any evidence that they considered the ritual function that some of these objects possessed and the consequences of removing them from that context?