Spoliation and Recovery of Art and Antiquities from Italy

Tuesday, 22 March 2022

Workshop roundup (by Eleni Vassilika)

Dr Barbara Furlotti (Courtauld Institute) spoke of the Italian laws against spoliation that were in place from the late 15th century. She described the case of Vincenzo Gonzaga and the collection of Peranda that Pope Clement VII declared should not leave Rome. Spies were ever on the lookout to report, because they usually received a percentage of the recovery. In the end, Cardinal Aldobrandini, the Camerlengo who had oversight of artistic patrimony, allowed their illegal export. To sum up, laws were in place, but enforcement was often lacking or contravened.

Dr Clare Hornsby (BSR) spoke of the classical sculptures acquired by George Bubb Doddington, a social climber, for his villa ‘La Trappe’ in Hammersmith. The villa was modified from the earlier restrained Palladianism by Servandoni to Roman extravagance requiring antique sculptures as decorative props. Initially, Cardinal Alessandro Albani, a collector himself, obstructed sales to Doddington but later facilitated them and even sold him his own sculptures. The gem collector Baron Stosch was one of the many spies who settled in Florence and enjoyed friendship and business with Albani through whom he was selling his sculptures to England. Such was the frenzy of dealing activity that it is not known which pieces might have come from the Giustiniani Collection. Doddington’s heir, Thomas Wyndham, sold the antiques at auction (Christie’s, 12/1777) that were possibly acquired by Thomas Barret (his Gothic house was modelled on that of Walpole’s Strawberry Hill), who had competed with Doddington to acquire from Albani.

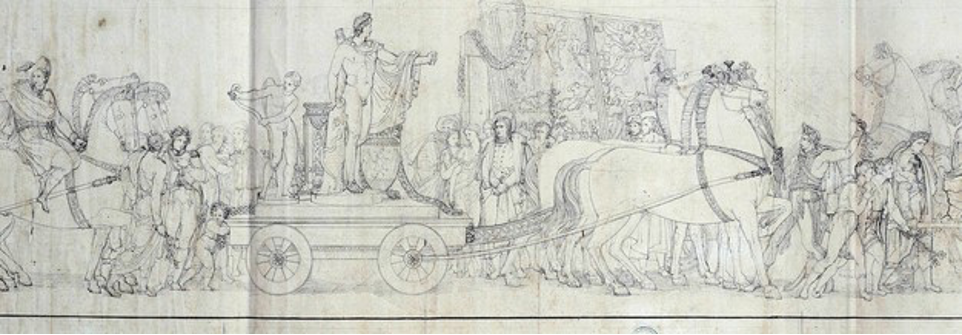

Dr David Gilks (University of East Anglia) discussed the French Republican narrative in which Papal dominion was represented as a decline and unworthy as heirs of antique Rome. The idea to make Paris the New Athens, existed before the French Revolution, thus legitimising the removal of antique sculptures from Italy and its destructive popes. A Napoleonic commission selected famous antiques such as the Apollo Belvedere and the Horses of St Marco. By 1800, one in six objects in the Louvre was fresh from Italy, much selected by Vivant Denon. Schiller, Goethe, Canova and others opposed this artistic plunder. The widely read armchair archaeologist Quatremère de Quincy, a covert royalist, claimed that plundering would undermine civilisation and that the papacy was a neutral moderating influence. Philosophical acrobatics claimed that plunder represented: 1) self-harm: why take cultural property from a people meant to be vanquished? 2) a specific status that belonged to locals and not to rulers; 3) loss of provenance by association with other objects (e.g. the Apollo Belvedere was a god in Italy, but only a piece of furniture in France). Along with numerous artists, including David and Thorvaldsen, he called for the restitution of 1000s of expropriated objects. Only about half of the paintings were returned. There were no treaties for the repatriation only ad hoc arrangements.

Valeria Paruzzo (University of Trento) described Venice under Austrian rule (1815-1866), a period when the religious fraternities were suppressed and the aristocracy was impoverished, resulting in the sale of artistic patrimony. With Napoleon’s defeat, there ended the blockades and the impossibility of movement of goods, also resulting in the arrival of an elite Prussian tourism. With the creation of a free port in Venice (1830), illicit traffic and smuggling became systemic, and ships’ captains colluded with the traffickers. Crimes of political dissent, freemasonry, spying and plotting were regarded graver than art trafficking, despite the public outrage. It is estimated that 3000-4000 works were exported. As copying was a legitimate academic exercise at the time, church paintings were replaced with copies to enable sales. The Austro-Hungarian criterion for export based mainly on ‘rarity’ allowed that many Carpaccios were free to go. There existed a large market for frescos resulting in destruction.

Dr Joanna Smalcerz (University of Warsaw) used a cartoon to tell of the American outrage at J. Pierpont Morgan’s aggressive art acquisitions (1912). Although the Cardinal Pacca Law (1820) was still in force, followed by the Nasi law of 1902 in many versions, lawmakers pressed for 20% rate payable on the value for an export license (eventually dropped). Dealers such as Stefano Bardini (1836-1922) kept up to date with the laws and case trials and arranged their lines of defense accordingly should they be caught and tried. Prince Sciarra sold paintings abroad and received three months jail and a fine of 5000 lire and the amount of the objects 1,266,000. The Avogli Trotti Trial (1907) for trafficking (by means of rolling canvases into the car exhaust pipe) failed because of his ‘unintentional contravention’ defense. Bardini was never fully prosecuted, as he played the system until the time limitations expired.

Prof. Irene Bald Romano (University of Arizona) explained that the Italian idea of Romanitá was equivalent to Hitler’s Greek ideal of beauty. However, antiquities seized in Italy by the Nazis has been largely ignored and repatriations have been slow: the sculpture of Artemis taken to Trier in 1943 was only repatriated in 2003; whereas the head of Drusus Minor was returned in 2017 by the Cleveland Museum. During WWII, 187 crates were sent from Naples to the Monte Cassino deposit. German propaganda proclaimed that the treasure was handed over to the Vatican authorities. In fact, of the 187 crates only 172 were delivered to the Vatican; the rest (of which 5 were composed of bronze and gold jewellery) were en route to Goering as a birthday gift. The Nazis also bought the famed Discobolos statue from the Lancellotti collection with Mussolini granting its export, rendering difficulties for its return (1950). Although the Etruscans were regarded as impure by the Nazis, gifts of vases with swastika motifs were made to Hitler. His projected Führermuseum for Linz was intended to include the Palestrina mosaic of the rape of Europa, which was shipped to Munich with an export license.

Steffano Alessandrini (Rome) showed numerous examples of antiquities bought by US museums starting with the Apulian Euphronios vase in the MMA sold by Robert Hecht, followed by the Morgantina silver treasure (MMA, 1981-82) the marble Aphrodite from the same site (Getty, 1988), and much material from Cerveteri in numerous museums (vases, antefix, cinerarium, a bronze Herakles etc.). He spoke of the life-size Hellenistic bronze statue of an athlete that was found in the sea by fishermen from Fano, Alessandrini’s own village, that went to the Getty (1977), followed by another life-size marble sculpture of the Doryphoros from Stabia sold to Minneapolis (1986). Also probably trafficked was Caravaggio’s Denial of Saint Peter in the MMA (1997). Alessandrini claims that numerous museum acquisitions are not on view due to their poor provenance.

Giuditta Giardini (art lawyer, Rome/NY) further elaborated on the antiquities and works of art that have been identified as Italian patrimony. She demonstrated how the trafficking network functioned with an organigram placing Robert Hecht at top of the pyramid. Giacomo Medici was responsible for trafficking works from central Italy and Gianfranco Becchina from the south. She described how transport was facilitated by breaking objects into small pieces for later reassembly. She spoke of money laundering by means of antiquities sales. Sacred Christian objects, including a tenth century missal could also be trafficked. Giardini ended the proceedings with descriptions of the legal mechanisms for restitution. These include major pieces such as the Getty Bronze and the Minneapolis Doryphoros, both of which are awaiting final Italian confiscation orders.