COLLECTING WITH A VIEW:

A series introducing the research and collecting interests of our Steering Committee members.

DR. THOMAS E. STAMMERS

1-What are you reading at the moment?

Reading is often tied to reviewing- and I agree to review lots to ensure that I do manage to keep up with recent scholarship. The most exciting thing I read last year was the new book by Iris Moon, Curator of Decorative Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled Luxury after Terror. It is about how the French Revolution transformed the market for, and meaning of, luxury goods, and places changes in the decorative arts at the centre of bigger shifts in French revolutionary culture. It argues- very persuasively -I think- that nowhere near enough attention has been paid to the changing forms of furniture, porcelain and silverware in comparison to the obsessive interest in the corpus of Jacques-Louis David. This is in part due to older forms of prejudice, but also reflects the fact that few specialists in the decorative arts have felt confident enough to make their subject the lens for thinking about bigger trends in revolutionary scholarship, such as ideas of gender and sexuality, authorship and representation, trauma and even currency reform.

The book is about collecting in quite an oblique way. It starts in 1793, with the great Versailles auction, and sees this dissolution as the starting point for various ways in which luxury production was reconfigured or reimagined. Of course, lots of scholars- including myself- have seen the 1790s as a key origin point in the history of collecting. Iris Moon’s book let’s us look at some of these changes from the perspective not of collectors but leading craftsmen from the old regime- including lesser-known figures like the goldsmith Auguste, the woodcarver Parent or the master of the arabesque Dugourc, who responded to this moment of dispersal and the undoing of the French monarchy. It’s a really conceptually sophisticated book, which covers lots of different disciplines and debates, and is unafraid of exploring some of the perverse elements of revolutionary culture. It’s published by University of Pennsylvania Press, who really have made a specialism out of publishing such handsome books.

2-What are you working on at the moment?

I currently have two main collecting projects, and shuttle a bit uneasily between them. The oldest is my ongoing work on the Orléans dynasty, the younger branch of the French royal family. Like Iris, I’m interested in the moments when monarchism is in crisis- especially after the regicide in 1793 (which is actually voted for by Louis XVI’s cousin, the Duc d’Orléans, Philippe Égalité), or 1848, when the first and only Orléanist King, Louis Philippe, is driven off the throne. I’ve been interested for a few years now in the Orléans family in exile in the half century after 1848- above all the new homes they create for themselves in west London, especially around Twickenham. You might know the octagonal tower of Orléans House; this is all that’s left of the house where Louis-Philippe and later his fifth son, the Duc d’Aumale lived (Aumale for over two decades). York House, now a building owned by Richmond council, was once the home of the pretender, the Comte de Paris.

I’m especially interested in how collecting was part of their strategies and experience of exile. Many people know about the extraordinary collections assembled by the Duc d’Aumale in London- especially the Old Master paintings and the rare books and manuscripts- and which are now housed in Chantilly. But much less work has been done on some of the other collections created in exile- like the wild taxidermy displays which later came to the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle- nor the way that collections from France were relocated to Britain during the long years of exile. By looking at these transfers, at how collections form and circulate, and how their meanings change depending on the French or British context, I really want to interrogate the politics of collecting, and think about how assembling all of these remarkable works of art co-existed with the desire to still appear as a royal house (and maybe one day regain the throne). It’s a story of failure- the Orléans return to France in 1871 only to be exiled again in 1886- but the collections became a key way for the family to commemorate and mourn their tradition. The recent sales of the Comte de Paris- like the big Sotheby’s auction in 2015- have made the collections of the otherwise very secretive family much better known, and are a great stimulus for new research.

The other hat I’m wearing is related to my position as co-investigator on the AHRC-funded project Jewish Country Houses: Objects, Networks, People(https://jch.history.ox.ac.uk). In it I’m exploring Jewish collecting with Silvia Davoli: as part of this work I published a special issue in the Journal of the History of Collections last year on German-Jewish collectors outside of Germany (co-edited with John Hilary). Silvia and I have also organised a set of conferences on Jewish dealers and on Jewish collectors which will form the basis of two edited volumes (https://jch.history.ox.ac.uk/event/workshop-jewish-collectors-and-patterns-taste-c1850-1930).

For myself I have a sabbatical coming up and want to write a book about the construction of the Jewish heritage in Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Weirdly, to me, this is a story that really is not very well known, outside of some important exhibitions (like the Anglo-Jewish Exhibition of 1887, or the Whitechapel show in 1906). I want to arrange the book around three big, intersecting themes- scholarship, politics and art- and think about different sites of Jewish heritage in and around London- from the Mocatta Library to the Mansion House and Guildhall art gallery, from Mayfair mansions to East End soup kitchens and country houses like Ascott- tracing how these sites were originally formed, and what they reveal about Jewish self-understandings. I am also interested in how these sites and collections were mobilised by the activism on behalf of persecuted Jews in the 1930s and 1940s. It’s a lot to do in one year but I’m starting with something manageable: at the moment I’m looking at the pioneering collection of Jewish bookplates!

3-Why do you think collecting is an interesting topic?

I love the fact that it is both a very old and a very new topic. Old, because for hundreds of years collectors themselves have been highly self-conscious about their ancestors and the pedigree of their treasures. Some awareness of collecting history has been integral to being a collector at all. But new, because it has only really become an academic field of study in the past fifty years. I’m very interested in the emergence of the subject in the 1970s and 1980s through my ongoing work on the scholarship of Francis Haskell- although of course he is only one of several possible founding fathers, along with scholars like Arthur Macgregor, Frank Hermann, Gerald Reitlinger, Kryzstopf Pomian, each of whom had very different methodologies. Then there are the great mavericks, like Mario Praz, or Maurice Rheims, who are hard to place in any fixed disciplinary tradition, not to mention the influence of literary depictions too. In light of how vibrant the field has become, it is striking that there has been so little work on its origins- although the range of different possible starting points is no doubt key to its methodological flexibility today, with scholars free to borrow approaches and concepts from the history of science, anthropology, econometrics, archaeology, psychology: the list is long, but all of it can be illuminating, depending on what one is trying to explain.

I came to the field through my training as a cultural historian. I was excited about how using new kinds of sources might allow you to shed new light on major events, like wars and revolutions but also allow you to think differently about the transmission of ideas. In my own research, collecting remains a key way to think about what individuals and societies value, as well as what they choose to pass on. Although it is often concerned with material things, I suppose I’m chiefly interested in what these things reveal about human values, and aspirations.

4- Do you collect? And if so what?

My own collecting is really rather modest. I buy the odd antique if I like the story behind it: I recently acquired a 1940s English portrait of an aristocratic grandmother and grandson because of its multiple Jewish associations (that I was probably the only one in the auction aware of); similarly, I particularly love a mahogany commode I bought in Newcastle partly because it once came from a stately home up there, containing trays used to serve dinners, and partly because the last owner kept some of her newspaper cuttings, thimbles and playing cards in a secret drawer inside. I don’t find such remainders morbid but rather find they humanise an object and make it more endearing.

I would collect more, but co-habitation in London has definitely forced me to rein in my habit. My big passion is books: not valued for their edition, or even for their condition, but more in order to create a kind of Platonic idea of a reference library, containing all the key books that speak to my interests, or unfulfilled ambitions (‘I would love to be the person who had read that book…’). I currently have about 6,000 books, very few of which are at all valuable, but which I can just about cope with as they are in different places in the UK. Having been bought a record player last year, I am now building a vinyl collection- but due to space it is really just some desert island classical, opera and jazz recordings, as well as some 70s albums I loved as a teenager.

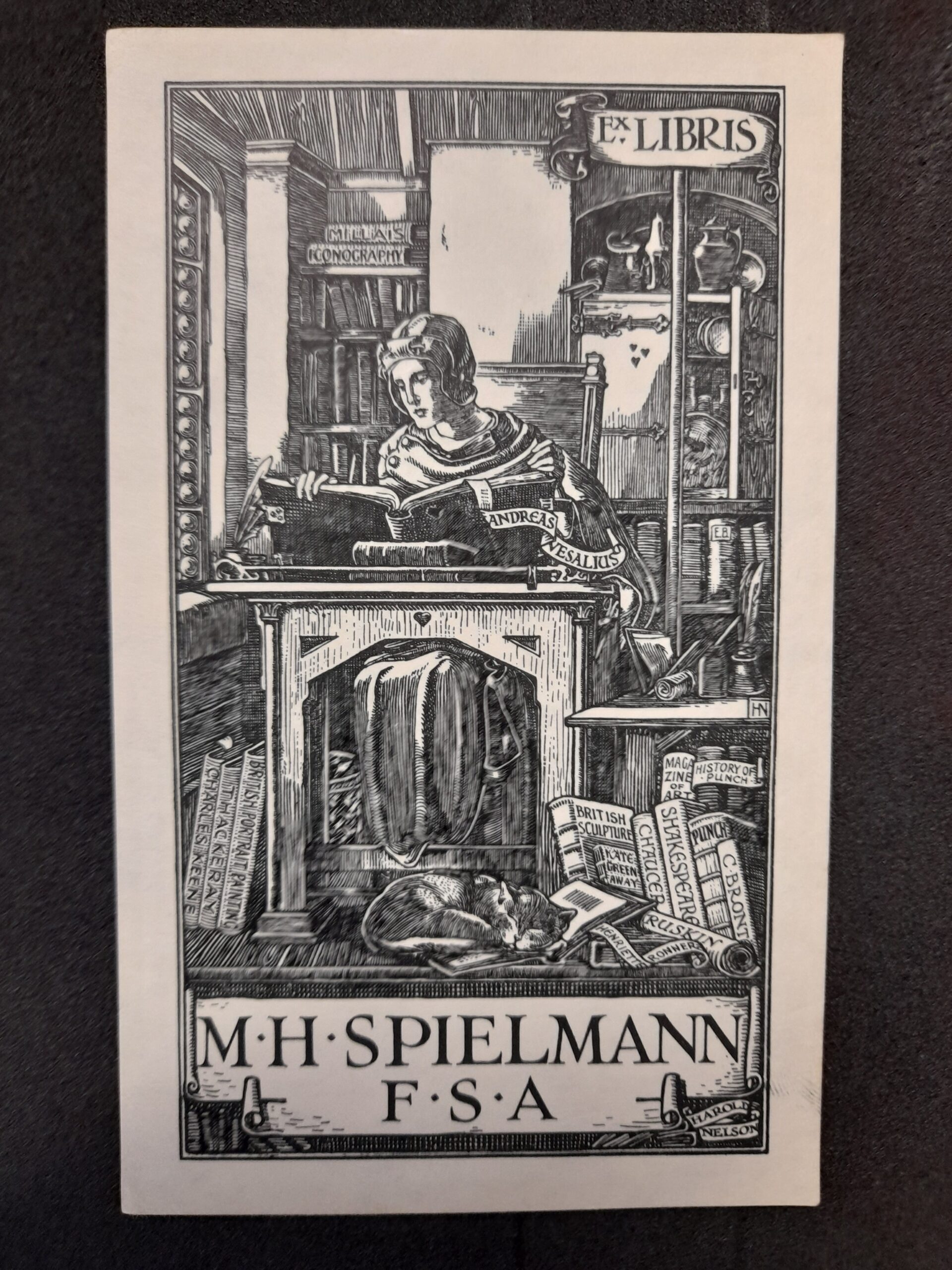

As I said, I’ve been doing some work recently on collections of bookplates, especially those owned by Jewish bibliophiles. For my 40th birthday last year my partner had a bookplate designed for me, which alludes to a lot of my interests in a single image, and now has made my sprawling mass of books into a single, named entity, a collection; this was not an entirely innocent gift, however, as I am sure the calculation was that by attaching an ex-libris to the books, I would find it easier to give them away!

5- If you could buy/collect anything in the world what would it be?

A brilliant question to which my vague answer would be- antiquities. Whilst I am attracted to the idea of having a really splendid Flemish tapestry, or a great French portrait in the style of Ingres, in truth I’d probably most like to have a great piece of Hellenistic sculpture. I love antique fragments, and it would be amazing to upgrade my rather battered selection of Victorian reproduction busts with something visually pleasing that is also thousands of years old. As someone who loves objects with stories, antiquities are in a class of their own.

wonderful to hear the personal thoughtful process behind a professional and collector

Dr. Stammers, I have read and reread your amazing book “The Purchase of the Past”. Although I am primarily a scholar of East Asian art, I have always been interested in the history of collecting and collectors, both royal and non-royal. And post Revolutionary France during the 19th century with its revolutions and upheavals in such a compelling area of study. I was led to your book after reading the heart-wrenching book by James McAuley “The House of Fragile Things”, which includes the tragic history of the Camando family. I had been to the Parc Monceau area to see the collection of the Cernuschi (Asian art), which was closed . I walked across the park to the Musee Nissim de Camando, probably one of the worlds best collections of “ancien regime” French furniture, decorative arts and paintings, assembled by Count Moise de Camando, and left to the State of France in the name of his son, Nissim, who died a hero’s death in WWI as a pilot. However the gifts of the Camandos (including Isaac who gifted the Louvre with major collections). Tragically Moises daughter, married into the prominent Reinach family, and who converted to Catholicism, thought even in 1942 as the roundups of Jews excelarated in Paris was blithely riding her horse in the Bois de Boulogne, thinking she was out of harms way. Alas, she and her children were deported on one of the last deportations to Auschwitz , where they perished.

At the entrance to the beautiful Hotel de Camando, there are two plaques: one honoring her brother saying “he died for France”, the other acknowledging the tragic end of the dynasty with a plaque that said “they died in Auschiwitz for France.” In his notes, McAuley says no- they died BECAUSE of France and the Occupation.

I look forward to following your work, and would highly recommend your book “The Purchase of the Past” to those interested in post Revolutionary (1793 ) France and the changing of hands of art and furniture from the ancien regime, from the First and Second Empires, and the reign of Louis-Phillipe.